This week in The Roundup: Elon Musk’s X/Twitter is slowing down links for companies he doesn’t like, an algorithm-free TikTok is coming to the EU and a crypto company wants your irises.

News

The war between Meta and Canadian news publishers has taken another turn, write Ismail Shakil and Zaheer Kachwala for Reuters. After Meta began blocking news content on its platforms, Canadian publishers have asked the government to launch an antitrust investigation.

According to the complaint lodged by News Media Canada and the Canadian Association of Broadcasters, the ban “seeks to impair Canadian news organizations’ ability to compete effectively in the news publishing and online advertising markets.”

The Canadian Competition Bureau has announced that it is now in the process of gathering information.

In another victory for First Amendment fans everywhere, free speech maniac Elon Musk has throttled links to sites he doesn’t like according to Gizmodo’s Nikki Main.

Links to news publishers like The New York Times and Reuters, as well as competitors like Facebook and Threads have all seen their load times from X/Twitter increase, sometimes to as much as 10 seconds.

This is just the latest retaliation on Musk’s part, against other companies. At the end of 2022, Substack was the object of Musk’s wrath for launching its Substack Notes feature.

Analysis

If there’s any one technical thing you know about TikTok, it’s probably the algorithm. It’s its special magic. Drawing from every piece of content on the network, TikTok uses that algorithm to recommend content – and it’s hugely successful.

But soon, users in the EU will have the opportunity to turn the algorithm off, reports Wired’s Nita Farahany.

The algorithm is so good because of the amount of user information that it hoovers up. However, in order to comply with the EU’s Digital Services Act, TikTok will have to offer users the ability to opt out. And if they do, no algorithm.

For Farahany, the broader issue is “cognitive liberty,” and this is just the tip of the iceberg: “Strong legal safeguards must be in place against interfering with mental privacy and manipulation. Companies must be transparent about how the algorithms they’re deploying work, and have a duty to assess, disclose, and adopt safeguards against undue influence.”

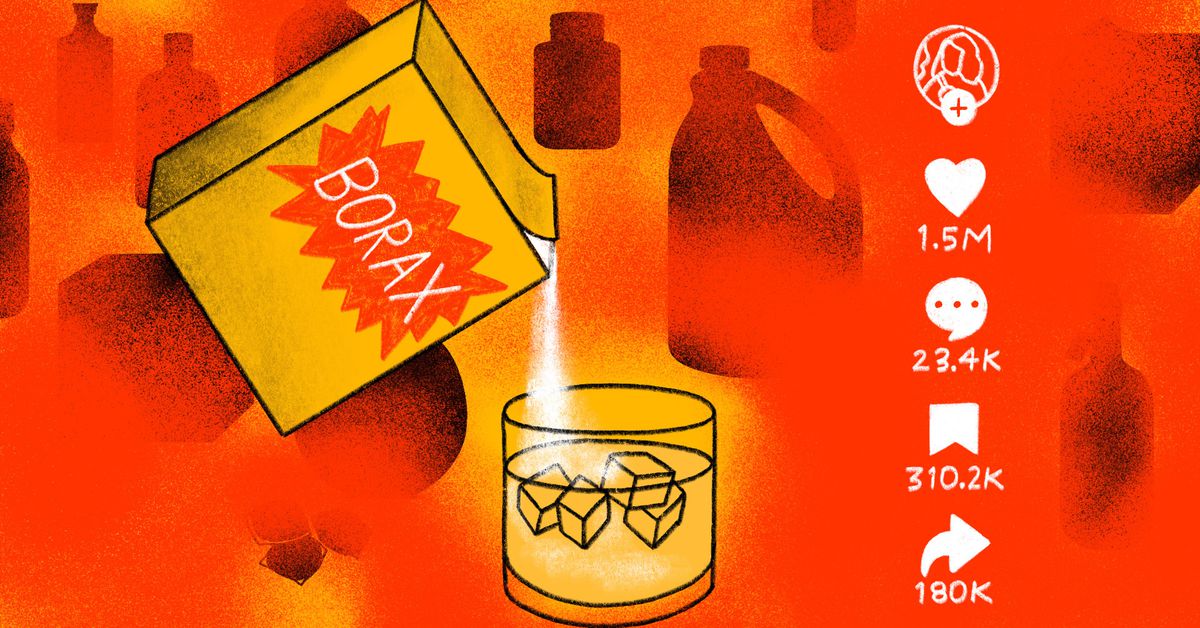

The #boraxchallenge is the latest social media stupidity, apparently. Big on TikTok, the challenge involves ingesting borax for its “health benefits.” It should go without saying that drinking, eating or even bathing in borax isn’t a good idea. But the borax challenge does say something about the nature of how disinformation spreads on social media.

As Abby Ohlheiser notes in this article for Vox, the problem with the kind of misinformation you see in social media trends is that “things go from ‘new’ to deeply familiar so quickly that it’s hard to find room for even well-meaning audiences to question their veracity.” And for TikTok, with a whole network worth of content to draw on, the problem is more acute.

AI

Here’s the grift: you develop a product that creates an issue, and then you turn round and create the solution. All for a price of course. So, it should come as no surprise that OpenAI’s Sam Altman has decided that he has the answer to the problem of cyber security that technologies such his cause. As AI becomes more sophisticated, we’re told, “custom biometric hardware might be the only long term viable solution to issue AI-safe proof of personhood verifications.”

That’s where Worldcoin comes in, Altman’s new dystopian crypto venture. Punters get their iris scanned by “the orb” in return for $60 worth of WLD coin (where regulations allow WLD). Orb operators are independent contractors paid to sign up people in their area, like an army recruiter or the Avon lady.

But is Worldcoin a financial product or a security one? Even Altman himself doesn’t seem to know, writes Forbes’ Richard Nieva. Instead, Altman’s personal credo according to a leaked speech he gave at a company meeting is “scale it up and see what happens.”

Biases present in data sets used to train deepfake detection tools risk concentrating their impact on minorities, writes The Guardian’s Hibaq Farah.

Existing technologies that are trained to spot deepfakes rely on techniques such as detecting heart rates or blood flow. This is, however, harder to do with darker skin tones, which could mean that rates of detection are worse. Without safeguards in place, therefore, the impact of fraudulent behavior may weigh heavier on minority communities.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/XWOBTN4OSZJC5O6DWRVTH6ZU6U.jpg)