We wanted to understand how technology leaders achieved individual accountability within their teams and organisations. Or if they even thought it was important?

Innovating, building and maintaining software is a team sport and it’s widely accepted that a foundational degree of accountability is essential for the effective functioning of any such team. The best teams even hold themselves accountable without requiring top down feedback. Beyond this basic agreement it would be ideal to understand the deeper relationship between accountability and business outcomes. Does more individual accountability necessarily lead to more impact and success? Other than the opinions expressed by respondents answering such a complex question fell outside the scope of this analysis. We have however started to peel back the digital curtain to reveal existing attitudes, patterns, and processes that define the current state of individual accountability within tech.

In a high accountability organisation the approximate relationship between an individual’s effort and their defined goals or business impact would always be clear. The relative impact of individuals within a team could be approximated. In a low accountability organisation it would be possible for an individual to regularly be doing work that brings little or no benefit to the team or business. In a worst case scenario a low accountability organisation would allow an individual to only contribute the ‘appearance’ of doing work, with no relevant business impact whatsoever. Every click, keystroke, and code commit could be telling a story of accountability – or the lack thereof.

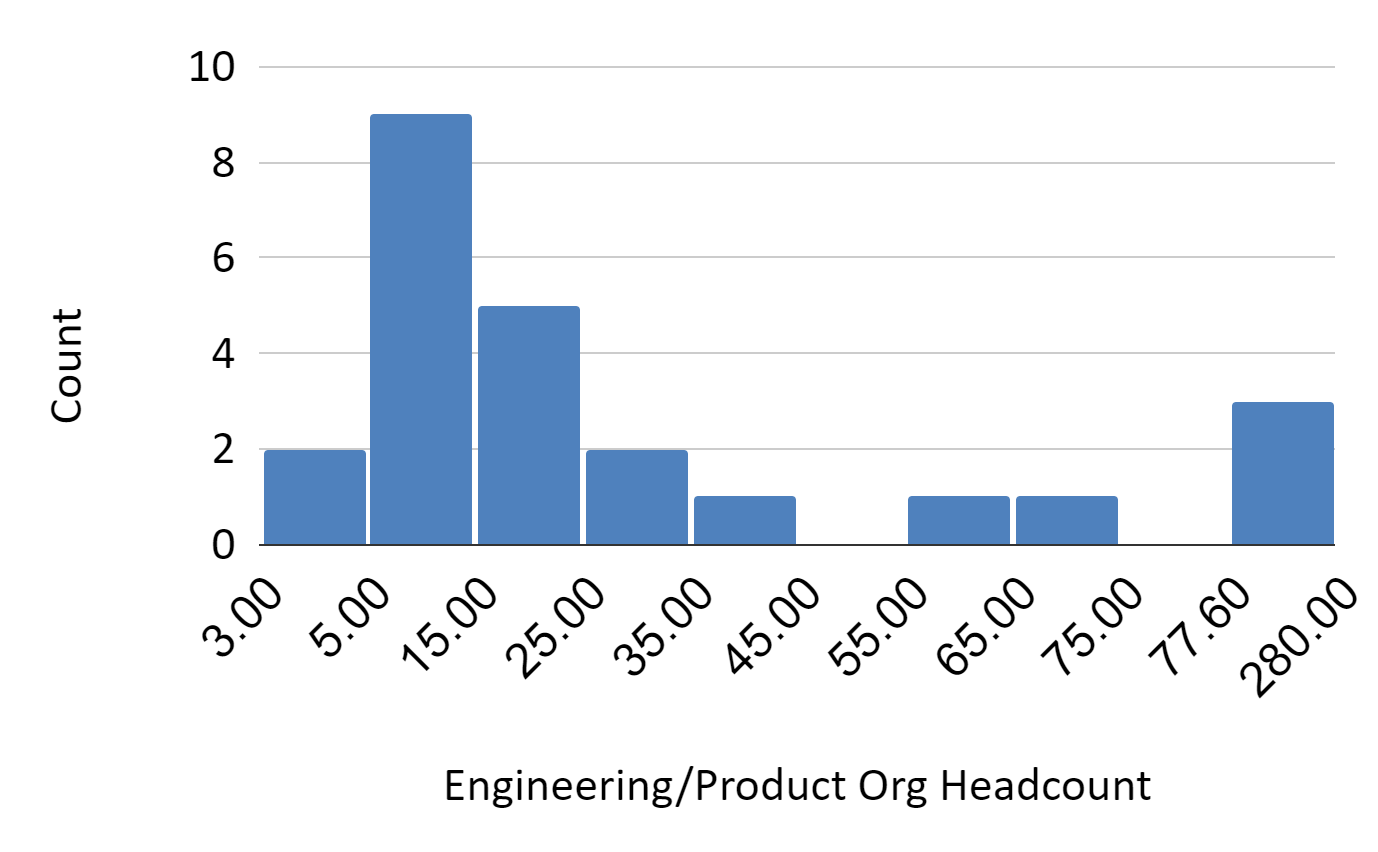

Figure 1 – What is the approximate headcount of your engineering and product development organisation? Please note the variable axis to help include outliers.

Our insights were drawn from 24 respondents. 19 of these were from technology organisations with a technology head count less than 50 people, with a median head count of 15, figure 1. The remaining 5 respondents were from organisations with a head of between 50 and 280. 14 of the respondents were CxOs and 7 were VP, Director or Heads of department.

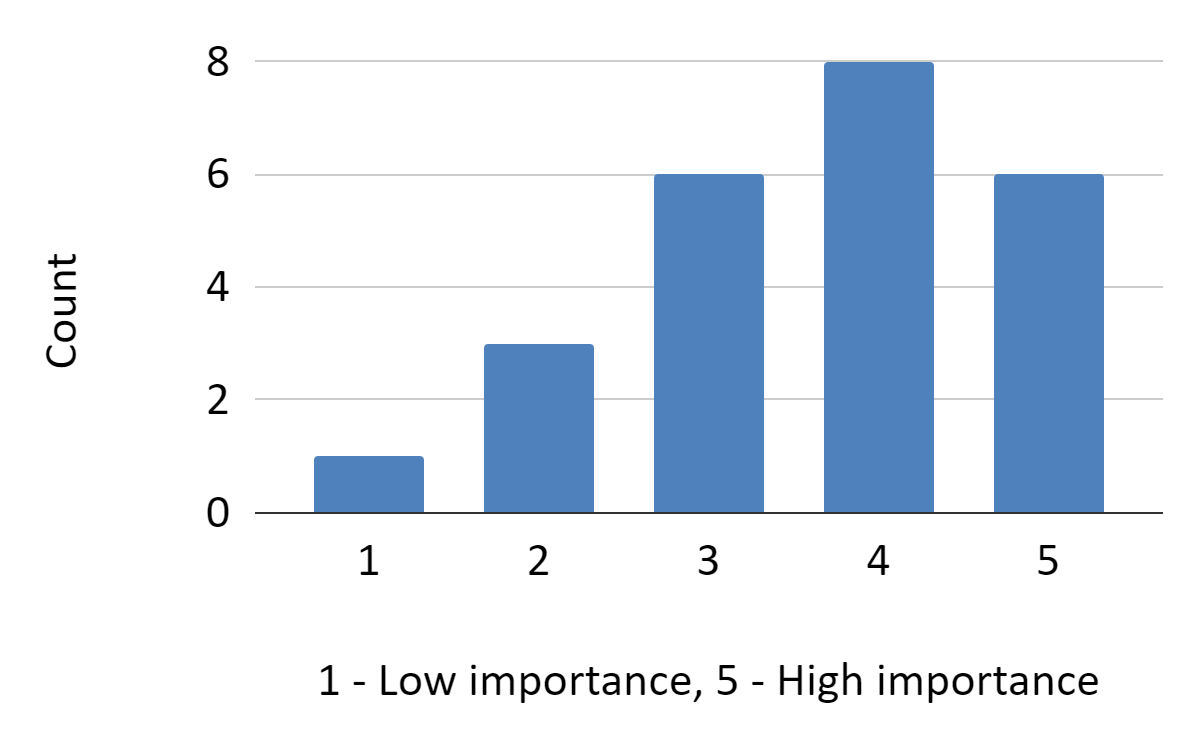

Figure 2 – How much importance is placed on individual accountability within your org?

58% of respondent’s organisations placed reasonable importance (4 and 5, figure 2) on individual accountability. Conversely 17% of respondent’s organisations placed minimal importance (importance 1 and 2) on individual accountability. The median importance given to individual accountability was 4.0, with a mean of 3.6.

Considering responses only from organisations with a technology head count larger than 50 there was a flatter distribution of importance placed on individual accountability, from 1 to 5. The median importance placed on individual accountability in these larger organisations was 3.0, with a mean of 2.6. This suggested that larger organisations placed less importance on individual accountability than smaller organisations.

Respondents which placed reasonable importance (4 and 5, figure 2) on individual accountability highlighted two common reasons for doing so: the expectation that there was a direct link between individual accountability and positive business outcomes and also for the healthy functioning of their teams, bringing “the best out of everyone”. Small teams in particular, often found in startups or consulting firms, necessitated a high degree of individual accountability to ensure impact was obtained from expensive and limited resources. In such settings, each member’s contributions were not only highly visible but essential for meeting business goals, as every person had “a large area of ownership” and was “lifting a heavy corner of the work”. Mistakes in teams with high degrees of individual accountability were reported as more likely to be seen as unintentional and by extension fostering a stronger learning culture.

Respondents which placed medium importance (3, figure 2) on individual accountability clarified this was primarily due to the fact that the greater focus was on everyone contributing to team outcomes. Providing the team achieved its objectives it was typically less relevant who contributed what. It was clarified that in a small enough “org individual accountability is how that happens”. Some expressed a desire to increase individual accountability but their organisation may not yet have “implemented an operating model that fully empowers individuals”.

Respondents which placed low importance (1 and 2, figure 2) on individual accountability elaborated to say this was due to “hierarchical structure and rigid processes”, a focus only on team outcomes ignoring the individual, outcomes being driven only by “the effectiveness of the manager” and high degrees of organisational “flux due to a variety of leadership-level factors that make the achievement of goals more challenging”.

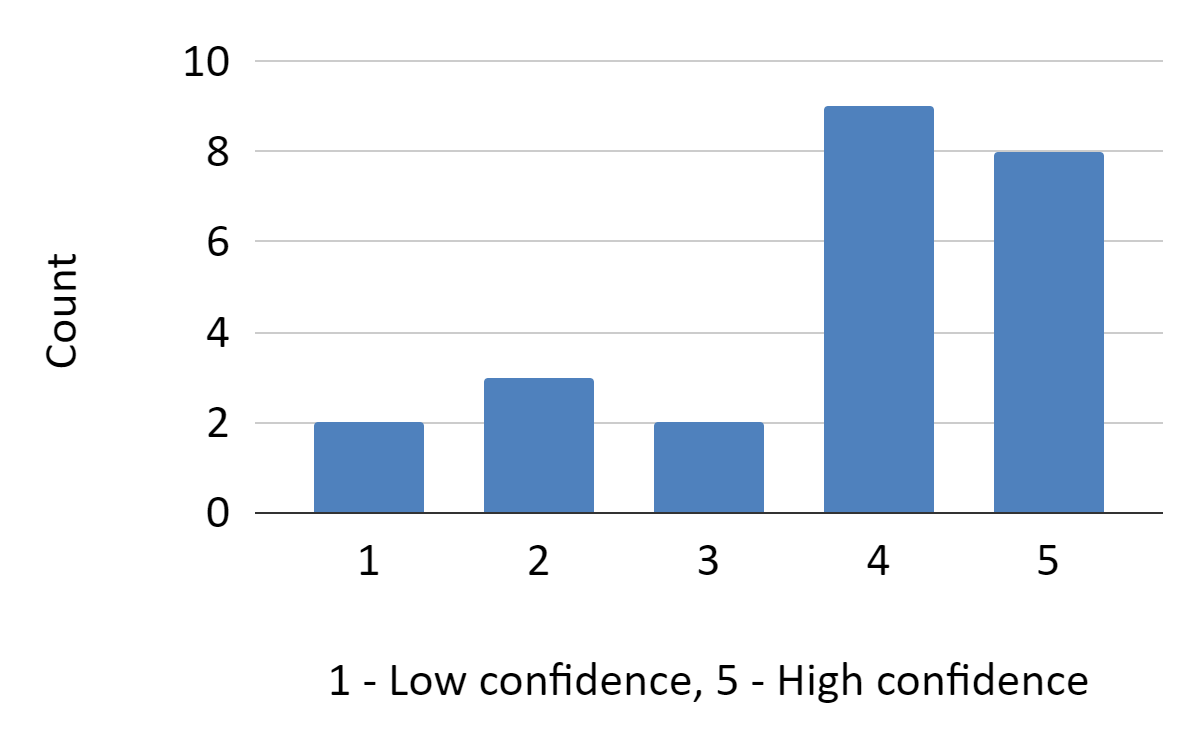

Figure 3 – If there was an accountability issue for a minority (<5%) of headcount within your org, how confident are you that it would be identified?

29% of respondents had moderate to low confidence (1, 2 & 3 in figure 3) that an accountability issue for a minority (<5%) of headcount would be spotted in their org. That’s approximately 1 in 3 organisations where individuals may increasingly be doing work that brings little or no benefit to the business. The median confidence in identifying an accountability issue was 4.0, with a mean of 3.8.

Considering data only from organisations with a technology head count larger than 50 people, there was a flat distribution if an accountability issue could be spotted. The median confidence in identifying an accountability issue for such larger organisations was 3.0, with a mean of 3.0. Being a larger organisation seemed to make it harder to recognise individual accountability issues.

A moderately positive Pearson correlation coefficient (0.64) was found between the importance placed on individual accountability and the expectation of being able to recognise an accountability issue for a minority (5%) of headcount. It would therefore be reasonable to say that placing more importance on individual accountability made recognising an issue for a minority of headcount easier.

Only one respondent said individual accountability was considered important in their organisation (4, figure 2) yet they had low confidence an accountability issue for a minority of headcount could be spotted (2, figure 3). Even though they had tried various approaches to increase accountability, for example implementing various development methodologies, “the line management structure [did] not allow managers expertise to appreciate individual contributions, leading to poor accountability”. The implication being that sufficient domain expertise was important to review the qualitative element of individual contributions reliably.

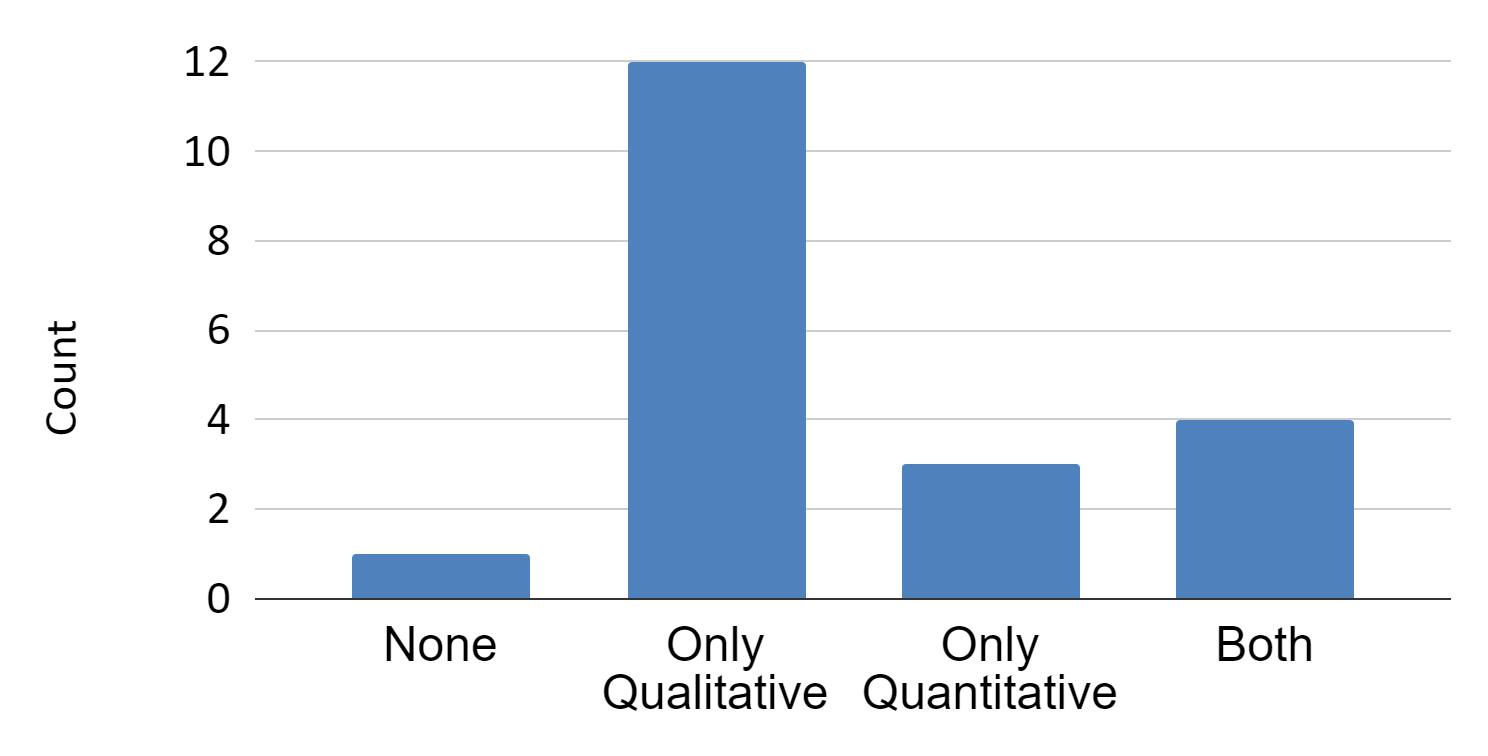

Figure 4 – If accountability is considered at least moderately important (3+, figure 2) what measures are used to try and achieve it.

Of 20 respondents who felt individual accountability was at least moderately important (3, 4 and 5, figure 2), the most common way of achieving it was using only qualitative measures (12 respondents). 3 respondents used only quantitative measures and 4 respondents used both quantitative and qualitative measures.

The qualitative measures which gave respondents the most confidence (4 and 5, figure 3) in spotting an individual accountability problem involved several touchpoints, across line managers, technical leads, scrum masters, product owners and code reviews. Regular communication amongst all stakeholders in regards to a teams’ and individuals’ impact allowed problems to be recognised early. Several respondents highlighted that a very transparent delivery process helped highlight when someone wasn’t taking accountability. For example indicators were that estimates were increasingly missed, progress or challenges were not being shared, “requirements [are] half-delivered” and “others need to step in to progress someone’s work”.

When a potential accountability problem was identified in such an environment respondents almost unanimously said it would be discussed in a 1:1, with an initial focus on ensuring the individual “has what they need to be successful”. A common pattern for helping achieve this big picture perspective, which was highlighted by a respondent, is 360 reviews.

Qualitative measures which gave respondents moderate confidence (3, figure 3) in spotting an individual accountability problem involved “goal-setting”, “stand-up updates”, sprint planning rituals and “following the time and money spent”.

Respondents who had low confidence (1, 2 figure 3) in spotting individual accountability problems reported using neither qualitative or quantitative measures. This suggested the lack of confidence may have been due to having no process in place to evaluate accountability.

Setting qualitative goals for individuals can be complicated due to the numerous ways unknowns can tip the balance in favour of over or under achieving a target. We asked our respondents how they might “distinguish between poorly set qualitative measures/goals and clever excuses?”.

Respondents answered that their solutions relied on a keen intuition for detecting insincerity, observing patterns of behaviour, potential repeated failure to meet goals, and performance over time. The judgement and experience of leads, subject-matter experts, and team familiarity ensured that excuses didn’t repeatedly succeed. One off problems could always be due to higher priority interruptions. Comparing effort and achievements against benchmarks, such as other team members, could help provide objective assessments.

3 respondents used only quantitative measures to achieve individual accountability. Organisation sizes for these respondents were from 4 people up to 280 people. They felt this gave them high confidence (4 & 5, figure 3) in recognising a problem for a minority of head count. The metrics they used were “business metrics impacted”, “number of items of work shipped and code contributions” as measured via GitHub activity, PR rate, deployments to prod, time spent in development and time spent in QA.

Extending this to respondents which combined both qualitative and quantitative measures. Respondents which had high confidence (4 & 5, figure 3) in recognising an individual accountability issue for a minority of head count focused on “amount of work delivered in a sprint”. Respondents were careful to highlight that although KPIs were not strict, allowing for error, the number of tickets delivered, code quality metrics, and code contribution metrics were highly relevant to them. One respondent elaborated to say they benchmark similar measures against open source projects with a similar team size and tech stack.

No quantitative measures were shared by respondents who had moderate to low confidence (1, 2 & 3 figure 3) in spotting an individual accountability problem.

We asked respondents for their closing thoughts around the topic of individual accountability within technology organisations.

It was emphasised by several that it was equally important to recognise the factors that fed into such situations. Prevention may be an equally powerful tool than trying to recognise an issue after the fact. Such respondents felt that providing company and team core values were strong, interview processes were robust, expectations were clearly set by leadership and everyone involved was a good fit for the role, for example not too junior, then the majority of common problems are rarer.

Respondents highlighted that increased individual accountability may also come with tradeoffs. It could “force greater granularity of boundaries which in itself may become an overhead” or if too much focus is on the individual rather than the team it “might lead them to try to game the system or care about themselves over the team”. If confirmed such tradeoffs make it impossible to make a logical argument for more individual accountability always being better to the extreme. These respondents argued for an important balance between individual and team accountability for business outcomes to be maximised.

In conclusion, our findings indicated that individual accountability within technology organisations was deemed essential by many leaders, particularly in smaller teams where every contribution is crucial. On average larger organisations placed less emphasis on individual accountability but also faced greater challenges in identifying issues when they arose. Only 17% of organisations placed minimal importance on individual accountability.

Effective measures to foster accountability included both qualitative and quantitative assessments, with transparent communication and regular feedback playing pivotal roles. Ultimately, while increased individual accountability can drive positive business outcomes, it is important to maintain a balance with team outcomes to avoid potential drawbacks such as undermining team cohesion.

We hope you have enjoyed the insights and analysis presented in this blog. If you have any questions or comments please let us know.

Anonymised responses – https://ebx.sh/uj12eC